Lost in Translation

Top 10 Most Noteworthy Rebranded Games of All Time!

Video games are universal, but the types of games people are interested in vary drastically from one region to the next. Themes that appeal to Japanese gamers won’t necessarily fly with American audiences (and vice versa), so it’s sometimes beneficial for a publisher to make alterations to a game before releasing it in a different region. There are many reasons why a publisher may feel compelled to rebrand games. In some cases, they may want to avoid paying for an obscure license that their target market is unfamiliar with. In other cases, a publisher can breathe new life into a game by attaching it to a well-known IP. There are even extreme cases where games are rebranded due to censorship guidelines. Regardless of the reason, this games looks at the ten most noteworthy examples of games being rebranded.

10

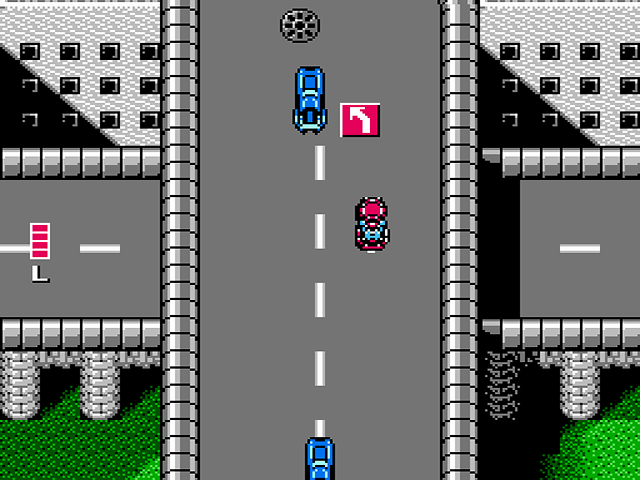

Super Spy Hunter

Originally: Battle Formula

No game on this list underwent fewer changes during the rebranding process than Super Spy Hunter. The original Spy Hunter was a classic 1983 arcade game that was developed and distributed by Bally Midway. The game mechanics combined elements from racing and action genres, and the premise involved racing down busy freeways and destroying as many enemy vehicles as possible. When Super Spy Hunter was released on the NES nearly a decade later, it retained most of the elements that made the original game so successful in the first place. Like its predecessor, Super Spy Hunter put players behind the wheel of a car loaded with gadgets and weapons. There was still a heavy emphasis on action, the game was still played from an overhead perspective, and the game was still intensely challenging. The weapons and enemies were a lot more varied in Super Spy Hunter, however, and the level layouts were more creative. It was everything you’d want a sequel to be. Having said that, Super Spy Hunter was never intended to be a sequel in the first place. The game was originally released in Japan under the name, Battle Formula. It was developed and published by Sunsoft, and Bally Midway had no involvement. Prior to releasing the game in America, Sunsoft obtained a license from Bally Midway to market the game under the Spy Hunter marquee. The game’s premise was so similar to its namesake that most fans didn’t even realize that it wasn’t a true sequel.

9

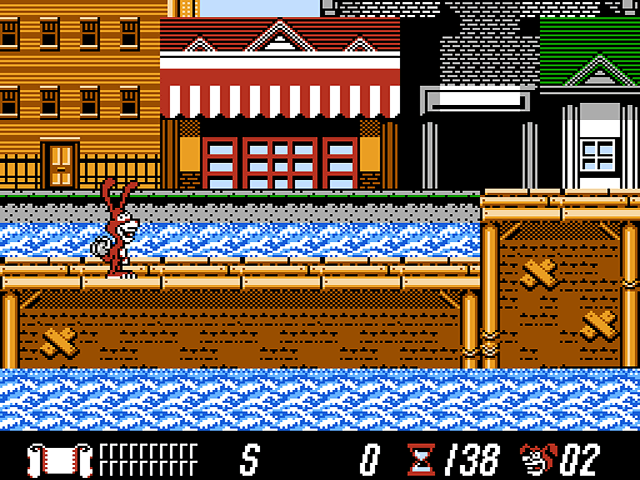

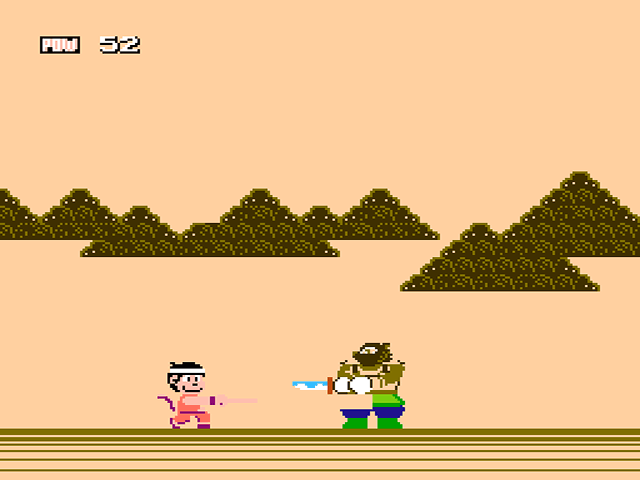

Yo! Noid

Originally: Kamen no Ninja Hanamaru

One of the main reasons why games are rebranded in different parts of the world relates to licensing issues. It doesn’t make sense to pay royalties for a property that no one in the region is familiar with, so it’s relatively common for licensed games to be generified in certain markets. The reverse is also true of course, and sometimes games are given a licensed makeover during the localization process. Yo! Noid is a side-scrolling platformer that was originally released in Japan as Kamen no Ninja Hanamaru (or “Masked Ninja Hanamaru”). For the western release, Capcom teamed up with Domino’s Pizza to promote the restaurant’s notorious advertising mascot. The plot in Yo! Noid is decidedly more pizza-centric than the game it was based on, but the differences between the two games are largely superficial. Hanamaru uses his pet hawk to attack his enemies while the Noid arms himself with a yo-yo, but the end result is the same. Likewise, it doesn’t really matter if you’re flying around with the assistance of a hawk companion or taking to the skies in a gyrocopter. It’s understandable why a publisher would feel the need to attach a license to the game, but it’s unfortunate that poor Hanamaru had to be shunned in such a disgraceful manner. He had “future mascot potential” written all over him, but Capcom kicked him to the curb and turned his game into a glorified advertisement.

8

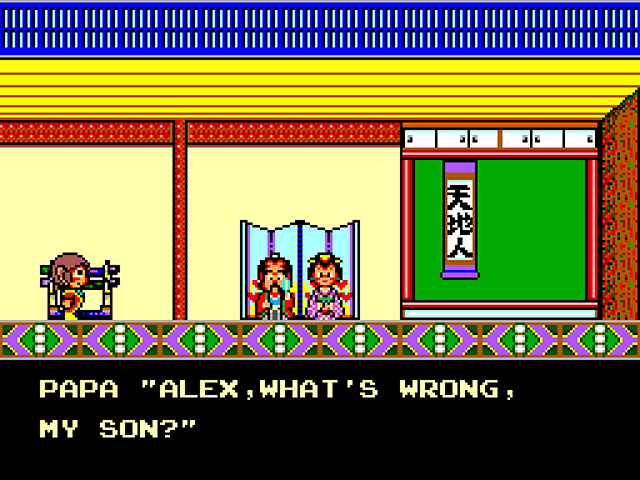

Alex Kidd: High-Tech World

Originally: Anmitsu Hime

Alex Kidd was the face of the Master System in the west and Sega was happy to brand games with his name even when they didn’t have anything to do with him. Alex Kidd: High-Tech World tasks players with going to an arcade to play the latest Sega games, but the original version was based on an anime called Anmitsu Hime that was set in feudal Japan. The manga dates back to the 1940s and is distinctly Japanese, but many details were changed for western audiences. The bakery was turned into an arcade, the ramen stall became a hotdog stand, and the ancient samurai sword was naturally replaced with a gun. (Video games, hotdogs, and guns… It sounds like Sega really understood American sensibilities!) I understand why Sega would drop the Anmitsu Hime license in favor of Alex Kidd, but they didn’t make an effort to place High-Tech World within the established continuity of the series. Aside from Alex’s long-lost father (who inexplicably makes an appearance at the beginning of the game), none of the characters from previous Alex Kidd games show up in High-Tech World. Likewise, the new characters that were introduced were never seen again. No one really cares about the lore of the Alex Kidd series, but the inconsistencies in High-Tech World were impossible to ignore.

7

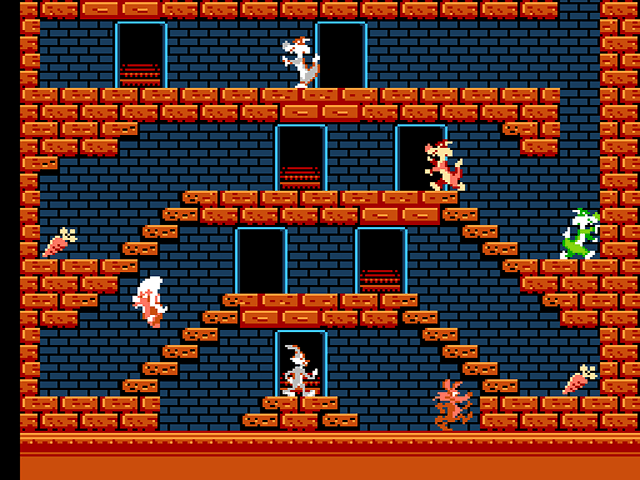

The Bugs Bunny Crazy Castle

Originally: Roger Rabbit

Kemco’s Crazy Castle franchise has produced many titles that have been rebranded in the west. The first game in the series was a Famicom Disk System game based on Who Framed Roger Rabbit? When Kemco brought the game to American shores, it was released as The Bugs Bunny Crazy Castle since LJN had secured the Roger Rabbit license. After picking up the rights to publish Disney games in Japan, Kemco released four Crazy Castle games for the Game Boy featuring Mickey Mouse. The first two games featured Bugs Bunny in place of Mickey in America, with the second being rebranded as a Hugo game for European audiences. The third Mickey Mouse game saw Kemco’s mascot Kid Klown being used in place of a licensed character in America, and the fourth Mickey game was rebranded with The Real Ghostbusters and Garfield licenses in America and Europe respectively. The final Mickey Mouse game actually retained its license for the American release, but the continuity was only temporarily. The next game featured Bugs Bunny again in America and Europe, but the original Japanese version featured Kid Klown instead. Bugs Bunny: Crazy Castle 4 (which was the eighth game in the series) was branded as a Bugs Bunny game in all regions. Kemco followed up with Crazy Castle 5 featuring… Woody Woodpecker? I give up. You shouldn’t need a codex to map out the timeline of a series.

6

Dragon Power

Originally: Dragon Ball

It was fairly common for games based on popular manga or anime franchises to be altered for their western releases in the ’80s and ’90s. The viability of these mediums had not yet been proven in America, so many production companies made no effort to bring their properties to western shores. In lieu of jumping through hoops to obtain licensing rights for franchises that were virtually unknown to Americans, most video game publishers simply removed references from their game. Bandai’s first Dragon Ball game was released on the Famicom in 1986, but the graphics were altered for the 1988 American release and Goku was given a headband so he’d be more in line with a Kung Fu stereotype. The gameplay was left in tact for the most part, but all Dragon Ball references were removed. Bulma was renamed “Nora,” Yamcha became “Lancer,” Oolong was now “Pudgy,” and the Dragon Balls were simply referred to as “crystalballs.” Some of the content was also edited for taste, and Master Roshi now craved sandwiches instead of pussy. The game was mediocre, so the fact that Bandai bothered to release it without a license attached to it is surprising. When you consider the current popularity of Dragon Ball in America, it’s almost hard to believe that publishers would go to such lengths to divorce their games from the franchise. Dragon Power was the first Dragon Ball game released in the west in any capacity, but American gamers wouldn’t see an official Dragon Ball game until Dragon Ball GT was released on the PlayStation in 1998.

5

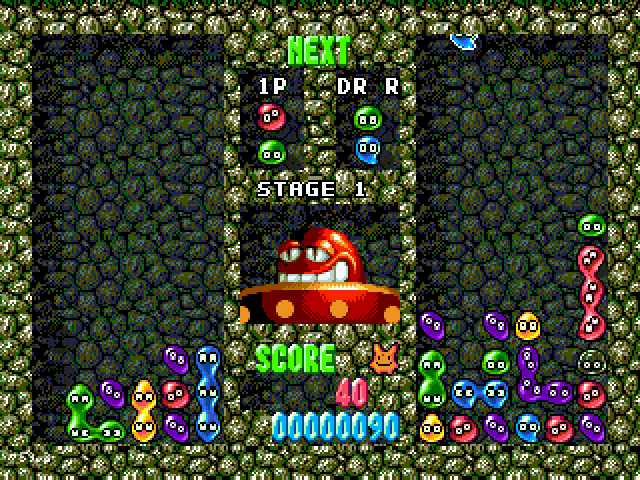

Dr. Robotnik’s Mean Bean Machine

Originally: Puyo Puyo

Following the unprecedented success of Tetris, “falling blocks” puzzle games were showered down on gamers like… well, like Tetris blocks. Out of all the Tetris-inspired games, none was more significant than Puyo Puyo. The concept of clearing away blobs by grouping them together in accordance to their color wasn’t exactly groundbreaking, but Puyo Puyo was the most competitive puzzle game of its era since it encouraged players to create chain reactions and clear out multiple groups with a single move. The first version of the game to be released in the west was rebranded as Dr. Robitnik’s Mean Bean Machine and focused on characters from the Sonic the Hedgehog franchise rather than the characters that had been created for the original game. Following Sega’s lead, Nintendo later rebranded Super Puyo Puyo as Kirby’s Avalanche for its western release in 1995. (Spectrum HoloByte also got in on the action with the release of Qwirks on for Windows and Mac OS.) SNK eventually broke from the norm when they released Puyo Pop on the Neo Geo Pocket Color in 1999, and it’s fair to say that the Puyo name has now been fully accepted by western audiences.

4

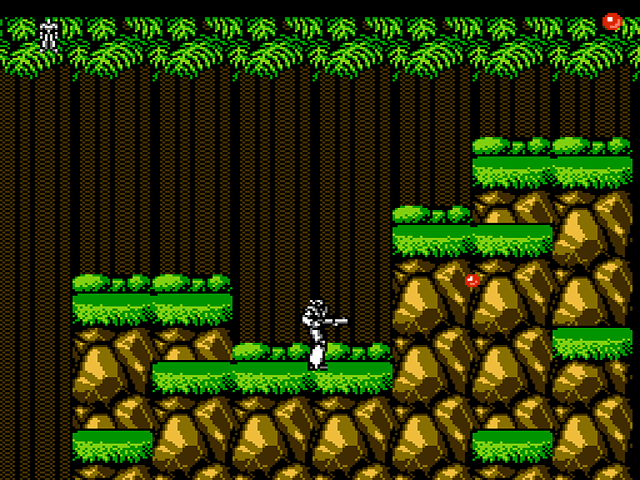

Probotector

Originally: Contra

Contra is a landmark action game that is widely regarded as one of the best co-op games of all time. The game took cues from 1980s R-rated action movies like Aliens, Rambo, and Commando, but the violence had to be toned down for European audiences since graphical depictions of human beings killing each other were frowned upon. Contra, Operation C, Super C, Contra III, and Contra: Hard Corps were all affixed with the Probotector title in Europe. These games replaced the human protagonists and enemies with robotic counterparts. Incidentally, Germany’s “Federal Review Board for Media Harmful to Minors” prohibited the sale of violent video games to children, so it was necessary for Konami to remove the human element from their games in order to circumvent the censorship laws. These kind of alterations were fairly common in America too (the 1987 Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles animated series re-imagined the Foot Clan as an army of robotic soldiers to avoid backlash from watchdog groups) but Germany’s censorship policies were state-sponsored and specifically prohibited “content which glorifies war.” These guidelines became less restrictive over time, and Konami abandoned the Probotector title beginning with the release of Contra: Legacy of War on the PlayStation. In the 2007 release of Contra 4, a Probotector unit was included as a secret character and appeared alongside the canonical human protagonists for the first time.

3

Tetris Attack

Originally: Panel de Pon

As with any great puzzle game, the basic premise of Tetris Attack is simple. In this case, the goal is to line up similar colors on a rising stack of blocks by swapping adjacent panels. The game’s biggest draw is its fast-paced combo system. There’s almost no limit to how many combos you can chain together, and very few puzzle games allow you to plan your moves so far in advance. The game was originally released in Japan as Panel de Pon and featured a cast of original characters. The fairies from the game apparently weren’t hip enough for the west, however, as Nintendo opted to replace them with characters from Yoshi’s Island when the game was released in America. Rather than relying on the power of Mario characters to drive sales, Nintendo went the extra mile by slapping the Tetris license on the game as well. (Tetris Attack doesn’t have a lot in common with its namesake and the Tetris Company even expressed their regret for allowing them to use the license in such a manner, but the game deserves a special mention on this list since Nintendo found a way to milk two cash cows at the same time.) The Tetris license makes it an unlikely candidate for re-release, but the game was rebranded several years later with the release of Pokémon Puzzle League on the Nintendo 64. More recently, Puzzle League has been released without the Pokémon or Tetris names attached to it. The original characters from Panel de Pon have been lost to the annals of time, but the game can stand on the merits of its gameplay and never really needed a license in the first place.

2

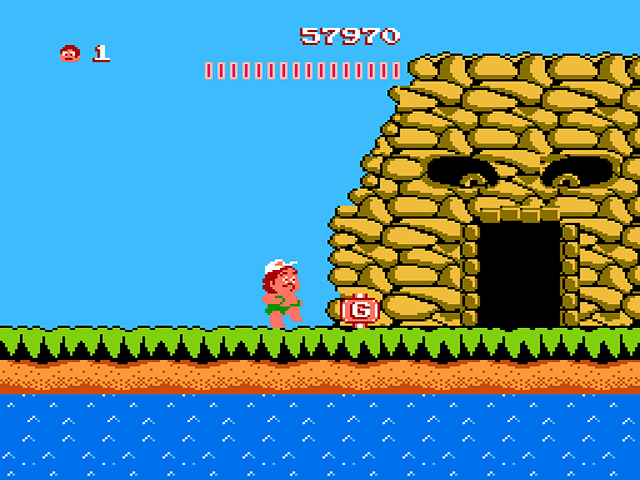

Adventure Island

Originally: Wonder Boy

Wonder Boy was a colorful platformer that centered around a brave caveman’s quest to rescue his girlfriend. The gameplay mostly involved killing snakes with stone axes, jumping over rocks, and riding a skateboard for some reason. (The notion of a caveman donning a helmet and knee pads is completely absurd, but it pretty much represents everything that is awesome about video games.) Wonder Boy was released in arcades in 1986 and was ported to Sega consoles shortly thereafter, but those who grew up playing the NES will notice that the game bares a striking resemblance to Hudson’s Adventure Island. As it turns out, a unique licensing agreement gave the publisher (Sega) the rights to the Wonder Boy name and character while the developer (Escape/Westone) retained the rights to the game itself. This allowed the developer to team up with Hudson to bring the game to Nintendo’s console. Adventure Island swapped out the main character, but the rest of the game was largely unchanged. Ironically, the gameplay that Wonder Boy established is more strongly linked with the Adventure Island series. While subsequent Wonder Boy games were drastically different from the original, Adventure Island spawned several direct sequels that stayed true to the original formula.

1

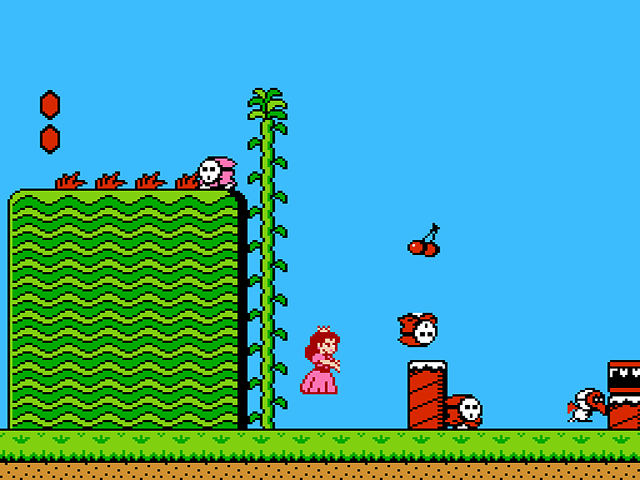

Super Mario Bros. 2

Originally: Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panic

Super Mario Bros. was the single biggest game of its era, so the expectations for the sequel couldn’t have been higher. Unbeknownst to most American gamers at the time, Super Mario Bros. 2 was released in Japan for the Famicom Disk System in June, 1986 – a mere nine months after its legendary predecessor. The sequel reused many assets from the original, and most of the music, sprites, and backgrounds were unchanged. The game could perhaps be described as an ultra challenging expansion pack of sorts. Most of the new concepts introduced in the sequel (including poisonous mushrooms, upside down pipes, wind storms, backwards warp zones, and the prospect of facing two Bowser’s at the end of the game) served to increase the game’s difficulty. Nintendo felt that the game was a little too difficult and were rightfully worried about how American gamers would respond to it. Instead of releasing the “real” Super Mario Bros. 2 in the west, Nintendo opted to give a makeover to an obscure Arabian-themed platformer called Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panic that was meant to tie-in with Fuji Television’s media technology expo. They replaced the original Arabian characters with Mario and his friends, added a dash button, and improved the animation. This rebranded version of Doki Doki Panic was released in America as Super Mario Bros. 2 in 1988. This version was actually much more successful than the “real” sequel, and was even released in Japan (as Super Mario USA) in 1992. American gamers would finally get their chance to play the original Japanese version of Super Mario Bros. 2 when it was released on Super Mario All-Stars in 1993.

Do you agree with this list? Let us know what you think by leaving a comment below. Your opinion matters!